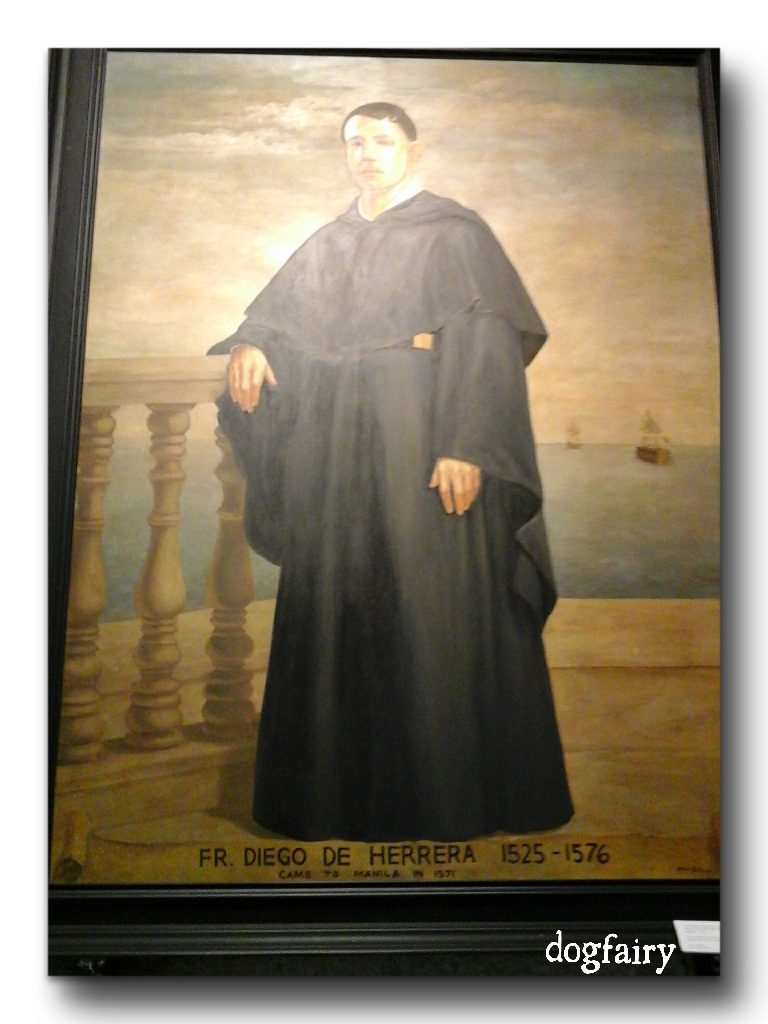

Fray Diego de Herrera, OSA: 1st Prior of the Sto. Niño Church

The Life of Fray Diego de Herrera and his martyrdom in the Philippines

Actual text translated into English from the “Conquistas de las Islas de Filipinas” by Fray Gaspar de San Agustin, OSA, pp. 749-759

The Life of the venerable Fray Diego de Herrera, and the unfortunate failure of the mission he was conducting in this Province

Of the lamentable events of Father Martin de Rada and Father Agustin de Albuquerque in the voyage they undertook to China, the end that the venerable Fray Diego de Herrera met was the most unfortunate and fatal, with the new operatives who accompanied him to these islands, in the propagation of the faith not only there but also in this archipelago and that of the vast empire of China, whose tragedy is retold but historians. However, I preferred to follow the narrative he makes it to the letter, as well as about the life of such an apostolic gentleman, as written by Fray Jose Sicardo in Adiciones a la Historia Mejicana.[1]

The venerable Fray Diego de Herrera was born of honorable parents, in an area of the Archbishopric of Toledo names Recas. He was the son of Miguel de Alameda and his legitimate wife, Juana Martinez. As good Christians, they educated their son in good customs. He grew so well-inclined that as a child, he would gather together others of his age, and would play at preaching them platitudes. Everyone admired his saintly propensity in this undertaking, and was of the opinion that God destined him for greater things, as time would prove when he would become a famous preacher in Spain, Mexico and the Philippines, where his efficacy and sweet words and sentences would enthrall his listeners. He was inclined to the religious state, and took on our habit at the convent of Toledo, where he professed his vows on March 10, 1545, even Fray Martin Claver in the history he wrote of our province in the Philippine states that he was a native of Medina del Campo and the son of our convent in Valladolid.[2] However, not even Father Herrera[3] found him among the sons of that convent, nor did I find him among the list I have of them. Our famous historian[4] states his teacher was Fray Jeronimo Roman, and since he would have taken his vows in our Haro [Jaro] convent on August 8, 1551 and the venerable Fray Diego on March 10, 1545, the time is proportionate to encompass the studies to which he admits, because before leaving the province of Castille, the venerable Fray Diego and expounded there with the credit corresponding to his great genius and knowledge due to his continuous studies; albeit with such subordinate resignation to his prelates that the enterprises of spiritual conquests were more the result of obedience than of the ardent spirit with which he undertook them.

Our Lord, the Father of families, called him to cultivate the vine of the Mexican empire, employing therewith the great talents with which he was gifted. In doing so, impelled by his ardent zeal, he went to Mexico and learned the Mexican language with such ease that in the provincial Chapter held on May 8, 1563 at the convent of Epazayocan, he was appointed preacher and confessor in the Mexican language. However, since it seemed to him to be too small a sphere for the ardor that filled his breast in the efforts of new conversion, he went with the rest of the religious in 1564 to the Philippines, where as apostles of those islands, they sowed the seed of the Gospel, converting innumerable residents. The venerable Fray Diego worked in this temporal conquest and spiritual work with his indefatigable spirit. The governor of the islands placed his confidence in his great talent. Thus, to assure success, he brought the priest with him in his pacification campaigns of Manila, becoming the instrument by which the local kings surrendered vassalage to our King, with some of them surrendering to the King of heaven and earth.

Upon the return to Mexico of the venerable Fray Andres de Urdaneta, the venerable Fray Diego was elected prior of the new convent of Cebu, and on this occasion achieved the baptism of Tupas, king of that island, as well as the conversion of other residents there. When the religious met there in 1569, they elected him their first father provincial. Returning from a visit to the provinces where the religious were spread out in the work of converting the pagans, he figured in a shipwreck, but was miraculously saved by God. Notwithstanding his great work for the good of the souls, he went back to Mexico once more to secure new recruits for the vine, and returned with two religious in 1570.

However, after continuing the evangelical work for some years with his indefatigable spirit, he realized that the harvest was growing and the laborers were few, so he returned to gather a greater number of them. When he reached the Spanish court, his proposals were so earnestly listened to by King Philip II that he was granted permission to bring forty religious, alone with many other benefits in remuneration for the numerous services our religious had done in both conquests of the islands. The father general of the order approved the separation of the province from that of Mexico. Thus, Fray Diego de Herrera was made up of forty religious, all very learned gentlemen. He also recommended Fray Juan de Velasco, who had been preacher of Toledo, and Fray Diego de Montoya who was in Cordoba, saying he was a good preacher. He also recommended good dispatch of establishment of that province. To further increase the number of evangelical workers in cultivating the new vine, the venerable Fray Diego presented a learned and discreet report – copies of which are found in Manila – urging King Philip II to have other religious order send representatives, which he did without hesitation, sending some religious from the order of Saint Francis.

While the venerable Fray Diego went to Spain, he asked the father provincial of Mexico top send some religious to help those who were left in the Philippines employed in the apostolic ministry. He did this carefully, sending Fray Francisco Manrique, Fray Alonso Heredero and Fray Sebastian de Molina in the company of Doctor Francisco de Sane, who was sent as governor of the islands. In a letter written to Fray Alonso de la Vera – Cruz on May 30, 1576, the governor informed him of his felicitous arrival in the company of the three religious, recounting how Father Molina died soon after arriving in Manila, and the great benefit to both the Catholic doctrines, as well as to the pacification of the natives that Father Manrique had achieved without fear among them, saying the following:

This office is that of an apostolate and requires the voice of one. Out of charity, Your Fatherliness sympathises with this land and everyone on it, since you well know that the Mexicans, being obedient like sheep, would rebel if the religious orders did not keep them peaceful and indoctrinated. Everyone is rebellious, because there is not a sufficient number of religious with the inclination to live among them and learn their languages; otherwise, they would all be peaceful.[5]

The venerable Fray Diego de Herrera reached the port of Vera Cruz on the eve of the festival of our Father San Agustin in 1575. Having brought the religious to Mexico from Spain, they arrived so tired from the journey and so sick due to the change of temperament that only six of the forty religious could continue the voyage, however, others from Mexico joined the voyage. There are reports of some in Mexico and Mechoacan which I found among the forty brought in from Spain, who are among the following of whom I give some details.

Fray Pedro de Vera

Fray Diego de Montiya

Fray Juan de Velasco

Fray Antonio de San Roman

Fray Alonso de Orozco

Fray Diego de Escobar

Fray Diego de Ordaz

Fray Juan de Ledesma

Fray Diego de Soto

Fray Pedro de Meneses

Of those who went to the Philippines with the venerable Fray Diego de Herrera, inclusive of those who came from Spain as well as those who joined them in Mexico, we only have news of the following:

Fray Lesmes de Santiago

Fray Francisco Bello

Fray Francisco de Arevalo

Fray Francisco Martinez de Biedma

Fray Juan de Santa Cruz

Fray Bernardino, or Bernardo, de Villar de Saz

Fray Rodrigo Nuñez

Fray Andres Marin

Fray Juan de Spinola

The venerable Fray Diego left with the above-mentioned religious. When they reached the port and embarked on the ship called Espiritu Santo or San Juan – as others say – they sailed on November 18, 1575, leaving Acapulco under good winds. But a hundred leagues from Manila towards the island of Catanduanes, whether due to fierce storms, too swift a current or carelessness of the pilots, the galleon was wrecked on the coast and dashed to pieaces. Since, on such occasions, many usually escape on smaller boats or on pieaces of wood or by swimming, about twenty to thirty people reached land, and among them were our religious. The barbarous islanders attacked and killed them with their spears and cutlasses. They watered the earth with the blood of the religious, recording on the sands the cruelty of the tyrants, and the constancy by which the religious tolerated such a cruel death at their hands. The barbarians attempted to hid their cruel deed for some time until, subject to vassalage and doctrine, they were educated and converted under the administration of virtuous clerics. Alonso Jimenez de Carmona was their parish priest for more than forty years. Later in Japan, he joined our order, and led an exemplary life when he lived a few years in the Philippines. In the end, he returned to Japan, where he died in piety, as shown in the customs and apostolic ministry he displayed throughout most of his life. Having the responsibility of the curacy of Catanduanes, he uncovered the details of the events from an old islander who was present during the tragedy. The old man recounted how the religious, having landed, went with the rest of those who were saved to a rock jutting out to the sea where they set up a cross. The islanders where hidden, and recognized them as religious because of the habits they wore. They decided to kill the religious before murdering the others since the religious were viewed as enemies of their laws, who had to teach them a new religion contrary to theirs.

Having agreed on this, the islanders approached them. A venerable ancient from among the religious, speaking Cebuano, came to meet them. This could not have been any other than the venerable Fray Diego. He asked them what they wanted. He inquired if the islanders knew they were religious and priests who exposed themselves to danger, hardships and the storms that had thrown them to the beach to save the islanders’ souls. Without waiting for any other explanations, the natives attacked the venerable Fray Diego like ferocious lions, impaling him with a lance, together with the other religious and seculars who escaped the shipwreck. The native storyteller claimed he took part in this spectacle. The rest, after having undertaken the bloody murders, retreated in fear of what the Spaniards in Manila would exact in retaliation against their cruelty and hatred of the Christian religion.

Because of the care by which the natives hid the events, it was assumed that everyone was lost at sea due to the shipwreck without anyone having reached land. In addition, the place and the circumstances of such a lamentable loss were definitely identified.[6]

However, in a book of Relaciones y Cartas which I saw in the real Colegio de San Pablo in Mexico, I read some writings by our religious of Manila wherein they gave notice of the spoils from the shipwreck that convinced everyone; especially since some Spaniards who went out to investigate the vent along the beach sent Fr. Francisco de Ortega a book of songs and many other pages – albeit useless – as well as some of the religious’ shoes, together with some ltters. Among these, two were found written by Francisco Curiel from Mexico. One of them was addressed to the religious and the other to the governor, notifying him that Fray Alonso de la Vera-Cruz was the provincial of Mexico and Vicar-General of India. Together with this evidence, more than fifty bodies of those who died in the shipwreck were washed up on the beach by the waves. Under this assumption, they bitterly lamented the imponderable loss of the religious whom they awaited in order to propagate the faith in those islands, those of Japan and in the extensive Chinese realm. The loss of the venerable Fr. Diego was deeply felt in the hearts of everyone, because he was one of the first apostles who converted and catechized many, among whom was the king of Manila, Rajah Soliman the elder, and lastly, as a good pastor, he had given his life in soliciting new religious to care for his sheep. He navigated more than sixteen thousand leagues – without counting the many he walked in his travels around the islands – seeking the conversion of the pagans.[7]

Some consider these apostolic religious as martyrs, because of the circumstances of their deaths and by their having suffered at the hand of the enemies of holy faith. Fr. Alonso Jimenez venerated them as such in the report made by one of his associates. They cannot be denied the crown they deserves, because they sacrificed their lives in serving God at the outset of 1576. And despite being impugned by some historians, as the voyage was reputedly set for China, it is not a culpable error to give the Philippines such a name, as it was introduced as sich since its discovery, as pointed out by Father Esteban de Salazar in his discourses and, to date, it is not known by any other name in New Spain.

To repay the many services contributed to the two Majesties, the Council of the Indies decided to appoint Fray Diego de Herrera as first Bishop of the islands. Having reached the decision in his person or in that of Fray Martin de Rada, it was resolved that Fr. Diego was to go without publishing the appointment so as not to delay him in Spain. The dispatches were to be sent to Mexico to be consecrated in that city, after which he would continue his voyage. He was in charge of taking the Bulls of Fr. Diego de Salamanca, prior of the convent of San Felipe in Madrid, as can be seen in the stated letter. However, since the venerable Father Herrera went ot the Philippines without staying in Mexico and perished before reaching the islands, the decision of the council was never effected.

[1] As far as the allusions that our author repeatedly makes to the Adiciones of Fr. Jose Sicardo, we refer the reader to what Fr. Gregorio de Santiago Vela writes about the same matters in his Ensayo, VII, pp 498-501.

[2] Martin Claver, Historia de Filipinas, See VELA, Ensayo II, pp. 13-14.

[3] TOMAS DE HERRERA, Historia del Convento de San Agustin de Salamanca, Madrid, 1652, pp. 178-196.

[4] ROMAN, Centurias, p. 133.

[5] This letter, as well as another directed to the Viceroy of New Spain opf a similar tenor, is preserved in the Augustinian archives, Aud de Filipinas, p. 6.